Thursday, July 09, 2009

McNamara: A Knave, not a Fool

Monday, June 29, 2009

The difficulty with writing about apocalypse

Wednesday, June 10, 2009

Right wing extremists

Saturday, June 06, 2009

The Underground, Underwater

When anti-narcotics agents first heard that drug cartels were building an armada of submarines to transport cocaine, they thought it was a joke. Now U.S. law enforcement officials say that more than a third of the cocaine smuggled into the United States from Colombia travels in submersibles.

An experimental oddity just two years ago, these strange semi-submarines are the cutting edge of drug trafficking today. They ferry hundreds of tons of cocaine for powerful Mexican cartels that are taking over the Pacific Ocean route for most northbound shipments, according to the Colombian navy.

The sub-builders are even trying to develop a remote-controlled model, officials say.

"That means no crew. That means just cocaine, or whatever, inside the boat," said Michael Braun, a former chief of operations at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration..."This is definitely the next generation of smuggling conveyance," said Joseph Ruddy, an assistant U.S. attorney in Tampa who prosecutes narco-mariners.

I am in the middle of reading a book called "Wired for War" which looks at the evolution of armed and autonomous robots in military operations. The author, mostly, looks at it from the perspective of established armed forces, but one can hardly ignore the more criminal possibilities. I know that martyrdom is portrayed as a virtue in reporting of terrorist operations, but that has to be a tough recruiting pitch. The assault on Islam by neo-cons was a failure, but I wonder if --when personal sacrifice is no longer a barrier to entry-- our current policy of peace through understanding will turn out to be yet another example of “fighting the last war.”

Friday, June 05, 2009

David Carradine, R.I.P.

"If you hang yourself by the neck, you don't need so much pressure to kill yourself. Those who get highly sexually aroused tend to forget this fact," Pornthip said.Pornthip?

Friday, May 29, 2009

When you've lost Peggy...

Thursday, May 21, 2009

Green shoots?

All the perfervid talk of the economy showing some "green shoots" because the second derivative of some key economic variables has turned positive is producing a classic suckers' rally. In order to believe that the economy really has found a bottom, you need to believe all of the following:

- That the stock market won't overcorrect to the downside, the way it has in every previous major recession of the last century. Hmmm:

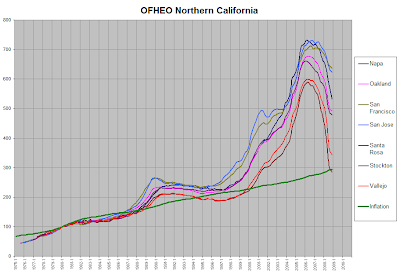

- That the real estate market is at or near the bottom. Hmmm:

- That the U.S. Fed has the information and tools to thread the needle between deflation and inflation: specifically, that Geithner and the other central bankers will (a) know exactly when to pull back on the massive amounts of liquidity they have injected into the markets, and then (b) actually be technically capable of doing so, and then (c) won't end up yanking the cord too hard.

- That the Japanese and the Chinese will keep buying Treasuries, come hell or high water.

- That all the various government stimulus bills are actually an efficient allocation mechanism and that there actually exists aggregate global demand such that the stimulus bills bring back jobs and growth in the medium term.

- That the intellectual awareness of the benefits of free trade will outweight the populist pressures of democratic polities during a major recession.

- That there are no big exogenous shocks, such as a major war in the Middle East, or a return of the swine flu in nastier pandemic form when the season returns in the Fall.

Bibi v. Barack

The NYTimes piece offers a pretty curious piece of reporting on the matter:

Mr. Netanyahu got his timetable. “We’re not going to have talks forever,” Mr. Obama said of Iran, assuring Mr. Netanyahu that he expected to know by the end of the year whether Iran was making “a good-faith effort to resolve differences.”The first thing that's striking about this is the presumption that the US-Israel relationship is now adversarial. But what's even weirder is the notion that Israel is somehow capable of "pressuring" the United States. How can Israel, which is the biggest aid recipient of the U.S. and has a population, economy, and military which are each about a 50th of the U.S.'s, "pressure" the U.S.? I suppose there may be an answer to this, but it's one that the pro-Israel crowd typically responds to with puerile screams that anyone who is critical of Israel's policies or wonders why the U.S. has unfailingly backed these policies is an "anti-semite."

But Mr. Obama did not get his settlement freeze. In fact, Mr. Netanyahu told him it would be politically difficult for him to halt the construction of settlements. That is a hurdle to the administration’s broader peace objectives because Israel’s Arab neighbors have characterized a freeze as a precondition for them to establish normal relations....

The two leaders set up working groups to deal with Iran, the Palestinian issue and Israel’s Arab neighbors. The groups will meet periodically, Israeli and American officials said. Agreeing to meet with Israel regularly to discuss the administration’s progress with Tehran keeps the pressure squarely on the United States, analysts said.

The second odd thing about this adversarial framing is the way that mostly unnamed sources allegedly representing both sides claim that their guy got the worse of the exchange:

“I’m asking the question, did our president get suckered?” said Martin S. Indyk [whereas] an Israeli official said [that] “Obama may be slightly less experienced than Netanyahu, but Obama knows exactly everything that the U.S. is doing."Pretty darn weird. Reminds me a bit of how both Reagan and Gorbachev aids claimed that the other guy was getting suckered during their Reykyavik summit--the one that basically ended the Cold War.

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Optimists are never pleasantly surprised

Even Goldman Sachs, widely regarded as the best manager of risk in the industry, did not foresee quite how bad things could get. The bank's most demanding pre-crisis stress test—known as the "wow," or worst of the worst, test—took the most negative events to have happened in each market since 1998 and assumed that they got 30% worse and all happened at the same time. That still wasn't pessimistic enough.That still wasn't pessimistic enough....

Monday, May 18, 2009

On regulatory capture, from finance to narcotics

Two archetypal scenarios for regulatory capture exist. The first is an underpowered, understaffed regulator working to control a wealthy, concentrated industry. In these situations, the sheer imbalance in resources means that the regulated parties can reward or punish the agency, but not vice versa. Predictably, rational bureaucrats will choose to cater their policies to the benefit of the subjects instead of suffering their wrath – recall, a regulatory job well done rarely carries any significant benefits to its engineers. The Department of Interior’s Minerals Management Service is a perfect example of a body that appears to have fallen prey to this pattern. Even a person of upstanding moral character can understand the difficulty of resisting the repeated entreaties of Exxon and the like for the sake of sticking to an unadulterated scheme of allocating oil and gas exploration rights. Someone sitting at the MMS desk may well wonder if anyone would ever notice a shift away from the prescribed approach towards one that favors the companies they deal with on a day-to-day basis. These incentives to cooperate exist even though the relationship between the regulator and the regulated parties is facially adversarial, with MMS holding rights that producers want but cannot get.Which raises an interesting question: which of these two archetypal forms does the regulatory capture of the drug enforcement bureaucracy represent?

The second standard scenario for regulatory capture takes place when the same agency identifies items to source from the private sector and supervises the production of these items. The Department of Defense springs to mind as an example. The Pentagon almost certainly has the best interests of the Armed Forces in mind when it sets out its procurement goals. The combination of public (“free”) money and a desire to avoid saying one’s coworkers and superiors made a mistake, however, means that projects live on even when they go horribly wrong. Private-sector contractors benefit from bloated budgets for littoral combat ships that suffer from fundamental structural defects (the program has since been scrapped), military officers occasionally pick up a kickback, and the taxpayer ends up footing the bill. The political prominence of the Pentagon aggravates the effects of regulatory capture, since colonels know they can fight off most allegations of inefficiency by claiming that a critic is unwilling to support the troops.

Monday, May 11, 2009

Another thing that's peculiar is that some nations, notably China and Russia, have banned the import of American pork. Many other countries are following their example. The flu is not spread through eating pork, and so banning it is an economic move and a symbolic gesture rather than a medically motivated public safety measure. But the popular appeal of the symbolism is irresistible: here they have a chance to ban American Swine!

American Swine come in three main varieties: the Hog, the Bankster, and the Neocon. The Hog is often a public safety menace, because factory farming practices result in large groups of immunocompromised animals confined in conditions that are perfect for incubating new diseases. These practices should be banned, and banning American pork around the world seems like a step in the right direction.

The Banksters who have crashed the world financial system through their fraudulent activities should be banned around the world as well. In addition, it would be nice if they were rounded up and herded into capitalist reeducation camps, where, thanks to hard physical labor, daily capitalist indoctrination sessions, and compulsory public self-criticism, they would, over the course of months or years, be reformed into model capitalists, ready to rejoin a free market economy. Perhaps our Chinese friends would be nice enough to send over some advisers, to help us set up these camps.

Unlike the Hogs and the Banksters, the Neocons who illegally murdered, imprisoned and tortured countless civilians across the world should be exported — extradited, that is, to stand trial at an international war crimes tribunal. The list is not that long: Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Rice, Gonzales and a few others. All the ones who "were only following orders" are not important enough. The United States government is bound by international treaty to either prosecute or extradite these people. Since prosecution in the US is unlikely to be carried out properly, extradition remains as the only option. President Obama's recent paying of lip service to this being "a nation of laws" is no substitute for action.

Of the three varieties of American Swine, the actual pigs seem like the least troublesome, swine flu notwithstanding. We should certainly do all we can to stay healthy, but in the meantime we should stay focused on doing something about the other two varieties of American Swine.

Saturday, May 09, 2009

Telling it like it is

Friday, May 08, 2009

Thursday, May 07, 2009

The bottom of the housing market?

At this point, a third of all mortgages are under water, which means that 1 in 5 of all homes in the U.S. are underwater. If you look at housing prices relative to headline inflation over the last thirty years, we're still way overvalued:

At this point, a third of all mortgages are under water, which means that 1 in 5 of all homes in the U.S. are underwater. If you look at housing prices relative to headline inflation over the last thirty years, we're still way overvalued: Now think about what this means for the holders of all the securities backed by these mortgages (e.g. the banks)... then think of what that means for the real economy.

Now think about what this means for the holders of all the securities backed by these mortgages (e.g. the banks)... then think of what that means for the real economy.

Money:

It's nice to get stuff for free, of course, and it's nice that more people can have their say in new media. And while some of our internet community is rampantly ideological, ridiculously inaccurate and occasionally juvenile, some of it's also quite good, even original. Understand, I'm not making a Luddite argument against the internet and all that it offers. But you do not, in my city, run into bloggers or so-called citizen journalists at City Hall or in the courthouse hallways or at the bars where police officers gather. You don't see them consistently nurturing and then pressing others—pressing sources. You don't see them holding institutions accountable on a daily basis.Consider this: the LA Times is the only news organization that still has a reporter covering the budget state budget (which is $131 billion this year, including a $40B deficit). If that guy goes, who will be watching to prevent corruption? And obviously the politicians and lobbyists know this too. In other words, you're one reporter away from, in essence, a complete lack of accountability on the part of the government of the sixth biggest economy in the world. As he Simon says elsewhere, I'll stop worrying about the fate of investigative journalism when I see Huffington Post bloggers showing up week after week to the city council meetings of smallish American cities.

Why? Because high-end journalism is a profession. It requires daily full-time commitment by trained men and women who return to the same beats day in and day out. Reporting was the hardest and, in some ways, most gratifying job I ever had. I'm offended to think that anyone anywhere believes American monoliths, as insulated, self-preserving and self-justifying as police departments, school systems, legislatures and chief executives, can be held to gathered facts by amateurs presenting the task—pursuing the task without compensation, training or, for that matter, sufficient standing to make public officials even care who it is they're lying to or who they're withholding information from.

Indeed, the very phrase "citizen journalist" strikes my ear as Orwellian. A neighbor who is a good listener and cares about people is a good neighbor; he is not in any sense a citizen social worker, just as a neighbor with a garden hose and good intentions is not a citizen firefighter. To say so is a heedless insult to trained social workers and firefighters.

So what is to be done? Simon suggests:

But a nonprofit model intrigues, especially if that model allows for locally based ownership and control of news organizations. Anything the government can do in the way of creating nonprofit status for newspapers should be seriously pursued. And further, anything that can be done to create financial or tax-based disincentives for bankrupt or near-bankrupt newspaper chains to transfer or donate unprofitable publications to locally based nonprofits should also be considered.I personally don't think that non-profit is any kind of solution: it already exists, and doesn't seem to be staunching the bleeding. Perhaps there might be some hope if all the newspapers could be given an anti-trust exemption to be allowed to collude on collectively creating a micropayment scheme for news content.

Lastly, I would urge Congress to consider relaxing certain antitrust prohibitions, so that the Washington Post, the New York Times and various other newspapers can openly discuss protecting copyright from aggregators and plan an industry-wide transition to a paid online subscriber base. Whatever money comes will prove essential to the task of hiring back some of the talent, commitment and institutional memory that has been squandered. Absent this basic and belated acknowledgement that content matters—in fact, content is all—I don't think anything can be done to save high-end professional journalism.

Thursday, April 30, 2009

I guess "rollback" ain't an option either

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

Cognitive Capture

internalized a worldview in which Wall Street is the central pillar of the American economy, the health of the economy depends on the health of a few major Wall Street banks, the importance of those banks justifies virtually any measures to protect them in their current form, large taxpayer subsidies to banks (and to bankers) are a necessary cost of those measures - and anyone who doesn't understand these principles is a simple populist who just doesn't understand the way the world really works.

Tea -- or Whiskey?

Sunday, April 26, 2009

The Taliban as modernizers

Friday, April 24, 2009

Thursday, April 23, 2009

The Bushies' Monte Cassino moment?

Line 1

During Bush's first term, the line of defense was: "We do not torture. There was no torture! You've got nothing to prosecute us for. Nothing!"

Then the Abu Ghraib pictures happened.

Line 2

Over the course of Bush's second term, the Bushies' main line of defense was: "OK, yeah, sometimes we torture. But it's our POLICY not to torture. You can't prosecute political leaders for what a few 'bad apples' do!"

Now the OLC memos have come out.

Line 3

That new line of defense is: "OK, yeah, yeah, torture was our policy. But torture WORKED. You can't prosecute political leaders for doing stuff that worked to keeping the country safe!"

We'll see if that line works.

Line 4

If it doesn't, you can already see the next (and presumably final) line of defense, which is even now being prepared: "OK, yeah, yeah: we do torture, and yeah, doing so was in fact our policy, and yeah, OK, it didn’t work. But we thought in GOOD FAITH that it would work. You can't prosecute political leaders for something that was done in good faith!"

Saturday, April 18, 2009

Quote of the Day

(The Irony of American History, p. 146-147)A democracy can not of course, engage in an explicit preventive war. [However] the power of such a temptation to a nation, long accustomed to expanding possibilities and only recently subjected to frustration, is enhanced by the spiritual aberrations which arise in a situation of intense enmity. The certainty of the foe's continued intransigence seems to be the only fixed fact in an uncertain future.

Nations find it even more difficult than individuals to preserve sanity when confronted with a resolute and unscrupulous foe. Hatred disturbs all residual serenity of spirit and vindictiveness muddies every pool of sanity. In the present situation even the sanest of our statesmen have found it convenient to conform their policies to the public temper of fear and hatred which the most vulgar of our politicians have generated or exploited. Our foreign policy is thus threatened with a kind of apoplectic rigidity and inflexibility. Constant proof is required that the foe is hated with sufficient vigor. Unfortunately the only persuasive proof seems to be the disavowal of precisely those discriminate judgments which are so necessary for an effective conflict with the evil, which we are supposed to abhor.

There is no simple triumph over this spirit of fear and hatred. It is certainly an achievement beyond the resources of a simple idealism. For naive idealists are always so preoccupied with their own virtues that they have no residual awareness of the common characteristics in all human foibles and frailties and could not bear to be reminded that there is a hidden kinship between the vices of the most vicious and the virtues of even the most upright.

Friday, April 17, 2009

The Torment of Secrecy

Money:

There are a lot of things that governments do, that aren't naturally or in the course of events immediately made public.

After all this [torture] began life as a covert action, whose definition is that the hand of the United States government is never acknowledged and the details of the operation are never revealed.

So, I don't think it automatically fits into the class of "the American people need to know."

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Quote of the Day

This guarding of our individualism against stratification insists not only in preserving in the social solution an equal opportunity for the able and ambitious to rise from the bottom; it also insists that the sons of the successful shall not by any mere right of birth or favor continue to occupy their fathers' places of power against the rise of a new generation in process of coming up from the bottom.

Wednesday, April 08, 2009

Climate Change - Leadership is Honesty

Tuesday, April 07, 2009

I love religion

When Jaaber Hussein signs an agreement with Israel's Chief Rabbis tomorrow, he will be inking the only Arab-Jewish accord sure to be meticulously observed by both sides. The deal will make him the owner for one week of all bread, pasta and beer in Israel - well a huge amount of it anyway. The contract, signed for the past 12 years by the Muslim hotel food manager, is part of the traditional celebrations ahead of the Jewish holiday of Passover. Jews are forbidden by biblical injunction to possess leavened bread, or chametz, during Passover and ironically an Arab is needed to properly observe the holiday. The agreement with Mr Hussein offers a way of complying with religious edicts without having to wastefully destroy massive quantities of food.

...

Tomorrow, Mr Hussein will put down a cash deposit of $4,800 (some 20,000 shekels or £3,245) for the $150m worth of leavened products he acquires from state companies, the prison service and the national stock of emergency supplies. The deposit will be returned at the end of the holiday, unless he decides to come up with the full value of the products. In that case he could, in theory, keep them all. At the close of the holiday, the foodstuffs purchased by Mr Hussein revert back to their original owners, who have given the Chief Rabbis the power of attorney over their leavened products. "It's a firm, strong agreement done in the best way," Mr Hussein said.

Saturday, April 04, 2009

How, Not Who

Justice Department lawyers concluded in an unpublished opinion earlier this year that the historic D.C. voting rights bill pending in Congress is unconstitutional, according to sources briefed on the issue. But Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr., who supports the measure, ordered up a second opinion from other lawyers in his department and determined that the legislation would pass muster.And now this:

The Obama administration is engineering its new bailout initiatives in a way that it believes will allow firms benefiting from the programs to avoid restrictions imposed by Congress, including limits on lavish executive pay, according to government officials...The administration believes it can sidestep the rules because, in many cases, it has decided not to provide federal aid directly to financial companies, the sources said. Instead, the government has set up special entities that act as middlemen, channeling the bailout funds to the firms and, via this two-step process, stripping away the requirement that the restrictions be imposed, according to officials.My ire of the past eight years was on, usually, both the what and the how. In one of these cases I am ok with the what, but the how, in both, is strictly Bush league.

Although some experts are questioning the legality of this strategy, the officials said it gives them latitude to determine whether firms should be subject to the congressional restrictions, which would require recipients to turn over ownership stakes to the government, as well as curb executive pay. The administration has decided that the conditions should not apply in at least three of the five initiatives funded by the rescue package.

Sunday, March 29, 2009

Obama at the G20

He found something antipathetic about the English lately. England was like a rich man after a disastrous orgy who makes up to the household by chatting with them individually, when it is obvious to them that he is only trying to get back his self-respect in order to usurp his former power.Which in turn suggests an interpretation of where the current crisis is putting the United States, in terms of imperial decline -- in some place analogous to where the European Great Powers found themselves after the war: bankrupt both financially and morally, but not yet at the point where another power is ready to formally replace them as the hegemonic center.

Friday, March 27, 2009

The Great Looting, Part II

The failure to do so shows how profoundly corrupt our political system is -- indeed, perhaps fatally corrupt.

Wednesday, March 25, 2009

Quote of the day

- Theodore Roosevelt, August 1907, commenting on bankers' responsibilities for the Panic of 1907

Tuesday, March 24, 2009

The great looting

The game of chicken that the American oligarchs are playing with the Obama administration is to say: "The only way we're going to stop looting the system is if you engage in forcible mass repression of capitalism (e.g. pay caps across all exec compensation, confiscatory taxation of the wealthy, etc.), which we're betting you don't have the brains, balls, or political capital to do."The state is now being asked not just to call off its regulators or give tax breaks or funnel a few contracts to connected companies; it is intervening directly in the economy, for the sole purpose of preserving the influence of the megafirms. In essence, Paulson used the bailout to transform the government into a giant bureaucracy of entitled assholedom, one that would socialize "toxic" risks but keep both the profits and the management of the bailed-out firms in private hands. Moreover, this whole process would be done in secret, away from the prying eyes of NASCAR dads, broke-ass liberals who read translations of French novels, subprime mortgage holders and other such financial losers....

As complex as all the finances are, the politics aren't hard to follow. By creating an urgent crisis that can only be solved by those fluent in a language too complex for ordinary people to understand, the Wall Street crowd has turned the vast majority of Americans into non-participants in their own political future. There is a reason it used to be a crime in the Confederate states to teach a slave to read: Literacy is power. In the age of the CDS and CDO, most of us are financial illiterates. By making an already too-complex economy even more complex, Wall Street has used the crisis to effect a historic, revolutionary change in our political system — transforming a democracy into a two-tiered state, one with plugged-in financial bureaucrats above and clueless customers below....

These people were never about anything except turning money into money, in order to get more money; valueswise they're on par with crack addicts, or obsessive sexual deviants who burgle homes to steal panties. Yet these are the people in whose hands our entire political future now rests.

Monday, March 23, 2009

A Postmodern Coverup

Friday, March 20, 2009

The End of Wall Street's Cognitive Hegemony

We have moved far beyond financial policy and into the kind of scandal that really gets taxpayers’ backs up. The greed of bankers slaps you in the face while the hubris of their leadership remains unchecked.Maybe we are finally witnessing the undoing of what John Robb acutely characterized as "an utterly complete cognitive regulatory capture of the US government" by the finance sector.

There is no sense of responsibility, no feeling of shame, no acknowledgment of any kind of mistake: read Lloyd Blankfein’s FT article again - or print it out and tape it to your wall. Because we now know, from the newly disclosed AIG counterparties list, that the wealth of Goldman Sachs insiders remains high solely because we saved their sorry bank, their failed risk management strategy, and their pretence of wisdom with our cash in mid-September.

This resentment against bankers pervades Congress, and even the Administration begins to get the message - being called "asinine" yesterday by Richard Kovacevich, the Chairman of Wells Fargo, may have helped underline to Treasury how deeply the bankers appreciate the help they have received. There can be no resolution and no moving on until there has been a proper congressional investigation, with full subpoena powers, into exactly what did and did not happen around AIG. This will take months and may well slow down the economy (Jamie Dimon’s clever point: if you vilify us, you will lose), but it is now inescapable. And, if channeled productively, this kind of hearing may lead to a better regulatory system (and smaller big banks) than the current anemic proposals on the table - as last weekend indicated, the G20 process is currently worse than useless on this issue.

The worthiness of the rich

For decades, the wealthy have been held up as people to be admired, victors in the Darwinian economic struggle by virtue of their personal ingenuity and hard work.As Michael Ledeen likes to say, Faster Please!

Americans consistently supported fiscal policies that undermined middle- and working-class interests partially because they saw themselves as rich-people-in-waiting: Given time, toil and the magic of compound interest, anyone could retire a millionaire.

That mind-set has all but been eradicated by the damage sustained by the average worker's nest egg, combined with the spectacle of bankers and financial engineers maintaining their lifestyles with multimillion-dollar bonuses while the submerged 99% struggle for oxygen.

(The price of admission to the top 1% income-earning club last year was roughly $400,000.) That may account for the near-total absence of public outcry over President Obama's proposal to raise tax rates on the wealthiest Americans -- except of course from the wealthiest Americans.

[snip]

The shift in sentiment should surprise no one. As the management sage Peter Drucker once predicted, "In the next economic downturn there will be an outbreak of bitterness and contempt for the super-corporate chieftains who pay themselves millions. In every major economic downturn in U.S. history the 'villains' have been the 'heroes' during the preceding boom." Drucker was speaking in 1997, two downturns ago.

[snip]

There's a social value in suppressing income inequality. In a country with only a slightly less ingrained tradition of civility than the United States, the AIG affair would provoke rioting in the streets.

"We live in a country with tranquillity and good feelings toward each other, and that's precious," says Robert Shiller, a Yale University economist and coauthor of Animal Spirits, a new book about the psychology of economics. In the current crisis, "there's anger and a sense of injustice taking hold, and it's not in the interest of wealthy people -- you don't want people on the poor side of town to be angry with you."

[snip]

Thanks to the financial crisis... the claim of the rich to play an indispensable role in the American economy will be treated with more skepticism than in the recent past, and their ability to preserve their loopholes and other advantages in the tax code will diminish

Will the economy suffer as a result? The experiment is about to begin.

Executive compensation

Just sayin'.

Update: Simon Johnson and James Kwak point out that retaining all those employees who made the messes probably isn't a good idea, anyway. Money:

When insiders have broken a financial institution, the most direct remedy is to kick them out. Traders are hardly in short supply, and you don’t need to rely on the ones who made the toxic trades in the first place. Companies must always plan around the potential departure of even their star traders, or they are certain to fail. A.I.G. does not need to keep all of its traders, especially since it takes far fewer people to unwind a portfolio than to build it up.

Thursday, March 19, 2009

Two thoughts on the AIG bonus outrage

The first is that I think part of what’s happening here is a corollary to Hitler's famous thesis about the role of "Big Lies" in politics (something Small Precautions has commented on in other contexts, as well). What Hitler acutely observed was this:

The magnitude of a lie always contains a certain factor of credibility, since the great masses of the people in the very bottom of their hearts tend to be corrupted rather than consciously and purposely evil, and that, therefore, in view of the primitive simplicity of their minds they more easily fall a victim to a big lie than to a little one, since they themselves lie in little things, but would be ashamed of lies that were too big.

By contrast, using taxpayer money to pay the executives bonuses at a failed company seems like mere everyday corruption, petty and small. Instead of a sign of the government's awesome power, it is a sign of the Obama administration's weakness and impotence, a point underscored by AIG's message to Geithner that heand the taxpayers could basically drop dead.

My second thought about the anger about the bonuses is that what's really in play here is not just anger at taxpayer money funding executive bonuses, but a deeper resentment about executive excess in general. Whereas the bailout money could be justified as a necessary payout to prevent the sucker from going down, and thus as having some positive social benefits despite its hideous price, it's almost impossible pettyfogging to try to justify AIG executive bonuses as being somehow about protecting the system. What's more, the claim that those bonuses are a necessary part of the system (which is the basic argument for why the bonuses need to be paid), then it seems to underline the essential corruption of that system.

And therein lies the real danger for the GOP's Richistan constituency: that one of the longer-term outcomes of the economic crisis is a cultural shift away from tolerance for the excesses of the corporate elite. Long-term economic downturns, particularly ones that seem directly linked to the excesses of the rich, usually do produce "Soak the Rich" demands.

Helicopter Ben

After yesterday's announcement that the Fed will be printing another trillion dollars, however, it occurred to me that the right way to envision Bernanke's use of the helicopter is not as a kindly humanitarian drop of necessary resources on suffering refugees, but rather something more like this:

Snark aside, isn't a U.S. hyperinflation rapidly becoming an inevitable surprise?

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

Here's an idea I like

Monday, March 16, 2009

Modernization Theory, Redux

The End of American Hegemony?

The problem with American foreign policy goes beyond George Bush. It includes a Washington establishment that has gotten comfortable with the exercise of American hegemony and treats compromise as treason and negotiations as appeasement. Other countries can have no legitimate interests of their own—Russian demands are by definition unacceptable. The only way to deal with countries is by issuing a series of maximalist demands. This is not foreign policy; it's imperial policy. And it isn't likely to work in today's world.Who cares if it works, though, if it makes you feel morally righteous?

Sunday, March 15, 2009

Snapshots from the future

Saturday, March 14, 2009

Requiem for a Business Section

The Washington Post, taking another step toward trimming the size of its newspaper, is folding its stand-alone Business section into the A section six days a week and drastically reducing the publication of stock tables...Columnists such as Steven Pearlstein and Joe Davidson will be moved..."What we're doing is eliminating things that readers can easily get elsewhere, where we don't necessarily bring value," Brauchli said.While the New York Times reports:

But in a change from previous downturns, CNBC is now a place for politics, to borrow a phrase from its sister channel MSNBC. The network’s journalists have been encouraged to speak their minds, making the line between reporter and commentator almost indistinguishable at times.Leading Nancy from Texas to opine:

"Get rid of the entertainment aspect and give us the news. Opinions and banter make me turn off the TV."Nancy is lying. I keep going back to Stewart Brand:

Information Wants To Be Free. Information also wants to be expensive. Information wants to be free because it has become so cheap to distribute, copy, and recombine---too cheap to meter. It wants to be expensive because it can be immeasurably valuable to the recipient.While the value may truly be immeasurable:

There’s also the not-inconsiderable question of capitalism’s ability to decide, if not on the value of a commodity, at least on some sort of price for the damn thing.Content is ubiquitous, commands almost no price, but nonetheless has a cost. To increase their returns the traditional media are shifting to context - bringing value in the words of the WaPo. But they are fighting the last war; context is also nearly ubiquitous, and since little of it is clever the price will bifurcate. To high-end prostitution:

Unlike most industries, escorts can charge higher prices when they are in greater supply. This is because price is one of the few metrics sex suppliers can use to convey quality. (In this way it is not unlike the hedge-fund industry.) The customer demographic is also wealthier, and a higher price deters customers from bargaining, which is considered poor taste.

The traditional media will never be able to compete on cachet and thus will have to be increasingly shrill and polarized to attract even a non-paying niche. On the high-end side a succession of saviors will continue to bilk the rich, both the new and the inbred. And all of this sound and fury will accomplish nothing, as Megan McArdle reminds us anyone who has:

"a good way to make money above and beyond broad, boring strategies like stock indices or bond funds, will not tell you about it."

Thursday, March 12, 2009

Of Bailouts and bondholders, pt 2

Given that common shareholders of AIG are already effectively wiped out (the stock has become a penny stock), the bailout of AIG is a bailout of the creditors of AIG that would now be insolvent without such a bailout. AIG sold over $500 billion of toxic credit default swap protection, and the counter-parties of this toxic insurance are major U.S. broker-dealers and banks.However, on further reflection about the political wisdom of insisting on transparency, I've become a little more ambivalent. On the strict merits, transparency is obviously a good thing, and I continue to support it.

News and banks analysts' reports suggested that Goldman Sachs (nyse: GS - news - people ) got about $25 billion of the government bailout of AIG and that Merrill Lynch was the second largest benefactor of the government largesse. These are educated guesses, as the government is hiding the counter-party benefactors of the AIG bailout. (Maybe Bloomberg should sue the Fed and Treasury again to have them disclose this information.)

But some things are known: Goldman's Lloyd Blankfein was the only CEO of a Wall Street firm who was present at the New York Fed meeting when the AIG bailout was discussed. So let us not kid each other: The $162 billion bailout of AIG is a nontransparent, opaque and shady bailout of the AIG counter-parties: Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and other domestic and foreign financial institutions.

But what I've also realized is that the political reaction to the revelation of the counterparty beneficiaries might not be the one that I might wish. Specifically, while there would undoubtedly be some left-populist outrage at the hedge fund plutocrats who are getting their taxpayer-funded checks from AIG, there would also likely be right-populist outrage at the foreign banks that are also inevitably getting some of this money. And that's a disconcerting prospect, since the one thing that would turn the current crisis from merely a possible Depression into a certain one, would be a series of jingo-inspired attempts to attack foreigners, including foreign banks, investors, and producers. Competitive nationalist financial reactions would really recapitulate the spiraling political economy of the 1930s.

The unfortunate fact of the current situation is that we must all hang together, or we will surely all hang separately.

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

Of Bailouts and Boldholders

If you've got a big insolvent bank and you need to make up a big hole on the balance sheet you've got, broadly speaking, four groups of people you can get the money from, or put a different way, who can take the hit: shareholders, depositors, bondholders and taxpayers.

Now, for most of these banks the stock price has essentially fallen to zero. So they're pretty much already wiped out. Not much to be accomplished there, although those folks want to hold on to their equity in the hopes that they may recover on the upside. Then you have the depositors. But in FDIC insured accounts, they've got a federal guarantee up to $250,000. And presumably those with really big sums on deposit have been proactive enough to spread their money around several institutions. So not much luck there either.

Which leaves you with bondholders (the companies creditors rather owners) and taxpayers. Now, on the one hand, this sounds like a no-brainer. If you lend money to a company that goes bankrupt, that's tough luck. Maybe you recover a percentage on the dollar of what you were owed. But too bad. Why taxpayers should cover those loses is really hard to answer. But let's try it.

The counter-argument is that if bondholders, especially the most 'senior creditors', take a big hit it, will create a big shock to the financial system worldwide, making bond-investing money extremely risk-averse for a long time and making the credit markets seize up again on far worse a scale than happened last fall in the wake of the Lehman bankruptcy.

A second issue is that a lot of these bondholders are other financial institutions, so you create a cascade of failure.

I am almost certain that many of the counterparties to AIG's credit default swaps, and thus the ultimate recipients of bailout expenditures, are hedge funds. There is no way to be sure because the information is confidential to AIG and the government has not forced public disclosure of those parties. Why am I so sure? Because 1) AIG was only one of a handful of entities that sold this type of protection and 2) the vast majority of protection buyers did not actually hold the underlying debt, but were instead making "naked" short trades betting that the paper would default, in other words, exactly the kind of trades hedge funds would make.In sum, taxpayer dollars are going, in large measure, to protect the profits (or at any rate staunch the losses) of hedge funds--organizations run for the wealthy by the superwealthy. The urge to go grab a pitchfork when you realize this becomes almost unbearable. It's hard to escape the conclusion that it turns out that the old socialists were right when they claimed that the main point of the state is to protect the property interests of the bourgeoisie.

If this is true, then bailout money is not being spent to shore up core capital ratios of our most important lending institutions, but instead is going to benefit hedge fund managers and their investors. Hedge fund losses, even up to the point of liquidation, do not threaten the overall economy. When Amaranth lost 9 billion within a matter of weeks a few years ago, the government did not step up. There was no systemic risk then when a few very wealth investors lost their shirts. Why should there be now? And, needless to say, counterparty risk -- the risk that a counterparty like AIG will not honor its contracts -- is a well-established business risk, one that investors pay their money managers to avoid. When the managers do not properly avoid the risk, the resulting losses are just like any other losses that a hedge fund may experience. Besides, the entire legal basis for the light regulation hedge funds is that their investors are savvy and wealthy, a group seemingly in little need of tax-payer-funded largesse.

Monday, March 09, 2009

How low the Dow?

Well, Warren Buffett said today that Berkshire Hathaway's 2008 profit fell by 62 percent, and its fourth quarter 2008 profit fell by 96 percent. If those are benchmarks for the profits of the entire industrial sector, we may be looking at an S&P500 bottoming out around 75, and the Dow in three digits, much as Professor Casti predicted.

(Comic footnote: In an apparent attempt to prove that American conservatism is the cognitive twin of Monty Python's Black Knight, AEI "scholar" James K. Glassman is still defending his claim that the Dow will soon hit 36,000.)

Saturday, March 07, 2009

Sign of the times

Update: In the Google Finance user comments on the Sturm, Ruger & Company stock, we have this lovely thread:

A: Whats up with this stock?B: Everybody is buying guns, seeds, and other survival neccesities [sic] because Obama is destroying the country. Don't believe me? Try buying some ammo in the south.C: The south. Try the northwest... I didn't even think about investing in firearms stocks until I went to our local gun store and saw the Obama full print with the caption "Employee of the Month" underneath

The worst case scenario for the meltdown

It is high time for the general population and socio-political players to get ready to face very hard times during which whole segments of our societies will be modified, temporarily disappear or even permanently vanish. For instance, the breakdown of the global monetary system we anticipated for summer 2009 will indeed entail the collapse of the US dollar (and all USD-denominated assets), but it will also induce, out of psychological contagion, a general loss of confidence in paper money altogether (these consequences give rise to a number of recommendations in this issue of the GEAB).This is couched as a prediction, rather than as a possible scenario, and as such I am not convinced. With that said, the case for the realism of this scenario is well made.

Last but not least, our team now estimates that the most monolithic, the most "imperialistic" political entities will suffer the most from this fifth phase of the crisis. Some states will indeed experience a strategic dislocation undermining their territorial integrity and their influence worldwide. As a consequence, other states will suddenly lose their protected situations and be thrust into regional chaos.

And just to be clear, when the authors talk about "imperialist political entities" being likely to suffer the most, they're talking about the United States. Even the NIC hasn't had the temerity to say this directly.

Dmitry Orlov looks more prescient by the day.

Thursday, March 05, 2009

Social decay

Tuesday, March 03, 2009

How low will equity markets go

The Dow, the Economy, and the Stimulus

Sunday, March 01, 2009

On Our Blindness

"Because of the Web, we've actually increased the number of words that we write about state government and politics," says Robert McCartney, The Post's assistant managing editor for metro news. Reporters who may find it harder to get stories into the paper write in more detail, often several times a day, for the Virginia Politics and Maryland Moment blogs.Again with the assumption that because something was in print it was seen; like the newspaper is a daily multi-vitamin that if swallowed distributes its contents equally throughout the mind. As is evident by McCartney's statement newspapers are increasingly posting "o'er land and ocean without rest" and contrary to Gibson's accusation of elitism they clearly "also serve who only stand and wait." The fact that this audience is blind is not a failure of the press, it is a failure of the people.

Critics say that shift serves only the elite that's intently interested in state news, not the broader audience. "The insiders are still getting a full report on the blogs, but the rest of us see only what we want to see instead of the news we need to see," says Bob Gibson, executive director of the Sorensen Institute for Political Leadership at the University of Virginia and a former politics reporter for the Daily Progress in Charlottesville.